America's "Golden Age of Illustration" - by Norm PlatnickWe frequently see references to America's "Golden Age of Illustration," but what exactly does that term mean? If you check that wonderful source of misinformation, the Internet, there seems to be a consensus that the Golden Age extended from 1880-1920 (see, for example, the entries at artcyclopedia.com, wikipedia.com, and illustration-art-solutions.com). What one doesn't find are any sources of evidence supporting that particular choice of dates, so I decided to try to collect some relevant evidence. The "Golden" term has at least two important implications, referring both to gold as an economic opportunity, and to gold as a color. The Golden Age was initiated not when color printing was invented, but when color printing techniques finally became inexpensive enough that publishers could actually start producing newspaper supplements, magazines, prints, and other wares that were illustrated in color and still inexpensive enough to sell widely, to the public at large. That created a "golden" opportunity for the artists. They could actually make a living from their painting; indeed, if they succeeded in selling their works to the largest publishers, they could even become famous and extremely well paid. So, given that interpretation, when did the Golden Age actually start, and when did it end? Although all three of the Internet sources mention book illustration, books with black and white illustrations were commonplace long before the Golden Age began. In my view, it was newspaper and magazine publishers who made the breakthrough - they were the first publishers to be able to produce items with color covers that immediately drew attention from the marketplace. So I decided to take a look at my own collection of magazine covers, and see what I could discover. Obviously, I don't collect the works of every artist who could be considered part of the "Golden Age," but I collect about 80 different artists, which I suggest constitute a representative sample, an issue I'll return to below. For the ca. 6500 magazine covers in my collection, I counted the number of covers that were published each year, and also the number of different periodicals on which they appeared:

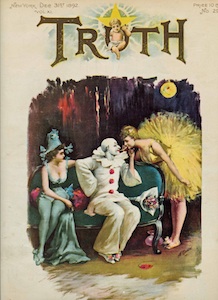

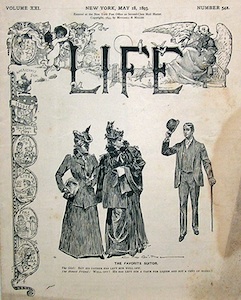

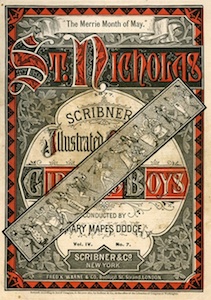

So, for example, in the early years, it is 1909 that shows the largest change from the preceding year; from that year, I have 115 different covers that appeared on 31 different periodicals, and the number of my covers stays above 100 for every year through 1939. The peak year was 1916, with 283 covers from 53 different periodicals. The earliest cover in my collection is a nice color cover by Albert Lynch that dates from October of 1890. However, it is not an American production; it appeared on a French magazine called Figaro. The first American cover in my collection dates from the last day of 1892 (see fig. 1), the New Year's Eve issue of a magazine called Truth. Truth was indeed one of the first major outlets of the Golden Age. The magazine was a weekly, and a typical issue had a color front cover, a color back cover, and a color centerfold (i.e., two pages, one outside and one inside, that were run through a color press), so that magazine alone needed over 150 paintings a year. Most of the covers I have from 1893 and 1894 are from issues of Truth that featured the artwork of Archie Gunn; some issues have both a cover and a centerfold painted by him. These data suggest that the standard references are wrong, and that the Golden Age did not start anywhere near as early as 1880. If I had to pick a single year to represent the start, based on the artists I collect, it would be 1893, not 1880. So the question is whether looking at other artists might justify the earlier date, and I tried to compile information on the earliest known covers by an additional 10 well-known artists. Among them, the earliest published magazine covers I could find date from the following years: Norman Rockwell - 1913; N. C. Wyeth - 1903; Howard Chandler Christy - 1899; Harrison Fisher - 1898; J. C. Leyendecker - 1896; Maxfield Parrish and James Montgomery Flagg - 1895; Albert Wenzell - 1893; Charles Dana Gibson - 1888; Howard Pyle - 1877. Thus, only two of these artists produced their first known cover prior to 1893. Charles Dana Gibson was probably the first illustrator of the period to become famous to the public at large. The "Gibson girls" that he created made his name, and work, widely known, enough so that several large books of his black-and-white illustrations were successfully marketed. He sold his first pen-and-ink sketch to Life magazine in 1886. Much of his early work appeared in Life; the development of the Gibson girl (see fig. 2) was closely tied to that magazine, and brought Gibson sufficient fame and wealth that after the founder of the magazine, John Ames Mitchell, died in 1918, Gibson became the magazine's editor, and eventually its owner as well. But Gibson's color work, such as a nice series of covers he did for McClure's in the early teens, came relatively late in his career, and I don't consider his (or anyone else's) early B&W work, including his early covers for Life, to be part of the "Golden Age of American Illustration." The other artist with a pre-1893 first known cover is Howard Pyle. Here again, that cover was in B&W, not color, and actually only a small part of that 1877 cover used Pyle's artwork (fig. 3). Pyle's success was primarily as a book illustrator, and his importance is largely due to his success as an art teacher and mentor to a wide variety of Golden Age illustrators, including Maxfield Parrish, N. C. Wyeth, Frank Schoonover, Philip Goodwin, and Jessie Wilcox Smith. Here again, I don't consider Pyle's early B&W magazine work relevant to the issue of when the "Golden Age" began. Newspaper and magazine covers are just one aspect of the "Golden Age," of course, so I also tried to see what I could learn from my collection of prints and calendar images by the 80 artists I deal with. Collecting accurate data there is more difficult than with magazines, the publication dates of which are obvious. Many prints, especially cropped ones, have no indication of either a copyright date or a date of publication, and even if they have such information, I would not necessarily entered the dates into my computer records. So my computer files have far less retrievable data on prints than on covers (roughly 2000 data points for prints). A thorough analysis would have to track the copyright date for each image. Nevertheless, the data I could collect show a similar pattern. The earliest print or calendar image in my computer files dates from 1891, the numbers don't reach 10 per year until 1901, and the peak years are 1907 through 1917, with outliers in 1925 and 1928:

So I conclude that, here again, there is no evidence that the "Golden Age" began any time in the 1880's, and there is plenty of evidence suggesting that 1920 does not represent a significant ending date, either. My magazine cover data indicate that Golden Age work continued to appear at least through 1937 or 1939. That was a surprise; I would have guessed that there would have been a sharp drop-off around 1935, when many major magazines began switching to color photographs for their covers. But in fact, illustrated covers by these artists continued to appear through 1951. For prints and calendar images, my counts remain above 10 for every year from 1901 through 1945, and don't consistently become single digits until 1955. Even though the peak years were prior to 1920, there was no significant decrease in activity from 1918 through 1930. My data suggest that the Golden Age started no earlier than 1893, and extended at least through 1939. So if I had to pick just years ending in zero, and a 40-year period, I'd suggest that the Golden Age should refer to the period from 1890-1930, rather than 1880-1920, and a reasonable argument can be made for extending the period at least to 1940 - in other words, 50 years rather than 40, and starting a decade later than conventional wisdom suggests. What do you think - have I overlooked important products of the 1880's that we should be paying attention to? I'm sure other opinions will find a welcome outlet in the newsletter, and you can reach me by email ([email protected]) or through my website at www.enchantmentink.com.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||